|

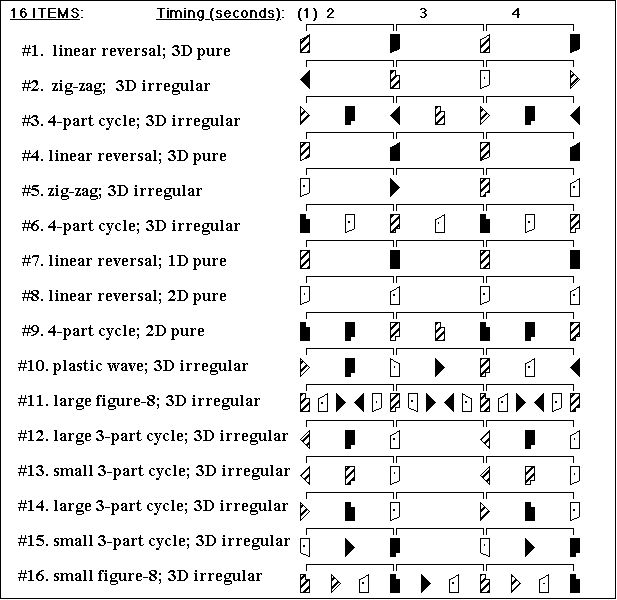

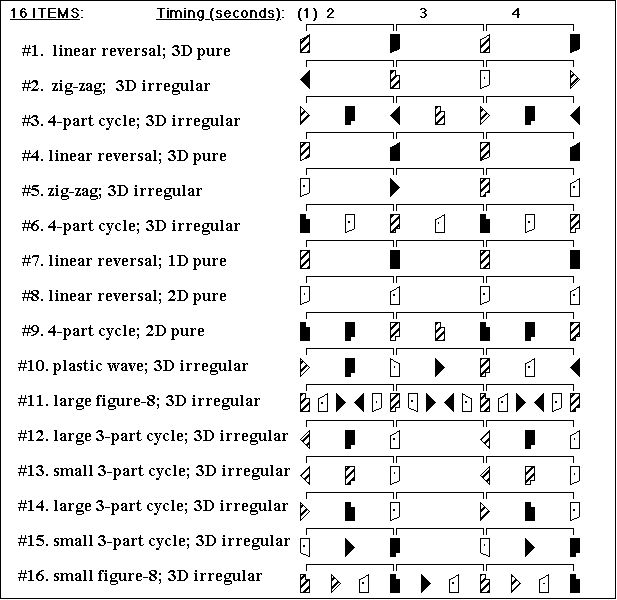

Figure IVB-11. Forms and orientations of the sixteen kinespheric-items. |

Hypothetical categories of kinesthetic spatial information are distinguished in dance and choreutics. These can possibly contribute to the need for defining a “class” of movement which has been identified as a fundamental problem in evaluating the schema theory for motor learning. Spatial perception research indicates that the primitive element of kinespheric poses is the straight body segment (eg. as in a “stick figure” representation of an animal’s body). Individual segments are organised into higher-order groupings (eg. ball-like, pentagon-shaped, “X”-shaped) according to the Gestalt principles of perceptual grouping. Motor control research indicates that the primitive element of kinespheric paths is the curved stroke between locations. Individual curved strokes can be organised into higher-order groupings (eg. straight paths, angles, loops, figure–8) according the possibilities afforded by kinesiological constraints. A method for developing a kinesiologically valid taxonomy of kinespheric forms is presented. Further refinements to an initial taxonomy developed here is a matter for future research.

Since visual and kinesthetic spatial forms can be easily recognised or produced regardless of metric variations, Bernstein asserts that they are mentally represented as “topological categories” which are embodied with slightly different metric variations on each successive physical execution yet the essential topological form is unchanged. Thus, Bernstein (1984, p. 109) describes the “co-ordinational net of the motor field . . . as oscillating like a cobweb in the wind”. This is virtually identical to the choreutic conception where kinespheric “natural sequences” are based on a contrast of “axial” versus “equatorial” shapes of motion, together with an intermediary “hybrid” and these topological forms are conceived to deflect across various polyhedral-shaped cognitive map-like images of the kinespheric network.

A question for the psychological study of kinesthetic perception and memory is whether kinesthetic spatial (ie. “kinespheric”) forms are actually cognitively organised into categories, and if so, what attributes determine category membership. Does the notion of kinespheric categories have any psychological validity?

The well established “clustering” or “subjective organisation” effect in verbal cognition research describes how items are recalled in an order which is indicative of how they have been cognitively categorised. It was hypothesized here that this effect might also occur for kinespheric recall. If items are grouped together during recall it may be indicative of the type of kinespheric categories which are used.

IVB.51 Clustering and Subjective Organisation.

IVB.51a Theory.

Bousfield and Sedgewick (1944) noted that during the free recall of words “successive associations tend to occur in clusters” (p. 153). They observed that when Subjects listed members of a category (eg. “animals”) the category members were spontaneously clustered together into groups of smaller sub-categories (eg. “domesticated animals”, “animals commonly in zoos”, or “related species in zoological taxonomy”). Many other experiments demonstrated this clustering effect which occurs whenever Subjects are free to recall a group of stimuli in any order (free recall). A variety of stimuli have been observed to be spontaneously organised into clusters, these include randomised lists of words from different categories (eg. animals, vegetables, human names, professions) (Bousfield, 1951; 1953), stimulus-response associated word-pairs (eg. table-chair; slow-fast) (Deese, 1959; Jenkins and Russell, 1952), sets of synonyms (Cofer, 1959), typical sequences of events in “script schemas” (Bower and Clark-Meyers, 1980; Rabinowitz and Mandler, 1983), and episodes within a story (Black and Bower, 1979). Clustering was also found to occur even when the group of items to be recalled did not obviously belong to any sub–categories but the words all appeared to be “unrelated” (Bousfield et al., 1964; Tulving, 1962).

In Miller’s (1956) famous paper he discussed this clustering effect in terms of “chunks” and describes how learning and recall include an operation of “grouping or organising the input sequence into units or chunks” (p. 93). Since this organisation of the items is imposed by the Subject, Tulving (1962; 1966) referred to it as “subjective organisation”. He discussed this organisation as consisting of “higher-order memory units” which are referred to as “subjective units” (S-units). Tulving’s “S–unit” is generally synonymous with Miller’s (1956) “chunk”.

The clustering effect was explained as occurring when Subjects bring related items together on the basis of their “inter-item associative strength” (Deese, 1959; Jenkins and Russell, 1952). Deese (1959) statistically defined this as “the average relative frequency with which all items in a list tend to elicit all other items in the same list as free associates” (p. 305). Wallace (1970) proposed a “contiguity principle” to explain clustering and subjective organisation. Jacoby (1974) described how this “implicit contiguity” occurs as a result of actively associating items together by “looking back through memory so as to bring the items together in mental experience” (p. 483). Thus, when a subject “thinks” about two items together, then a contiguity of experience is created between these items, even if the items do not have an obvious association. When items are “experienced” together in this way they also tend to be recalled together.

IVB.51b Correlation of Subjective Organisation and Learning.

The amount of subjective organisation is usually correlated with the amount recalled (Anderson and Watts, 1969; Tulving, 1962). This correlation has been explained in several ways.

Deese (1959) asserted that if there is a high degree of “inter-item associative strength” that each item will serve as a cue to assist in recalling the other items. That is, “recall is good or poor depending, then, upon the tendency of free associations from items within the list to converge upon other items within the list” (p. 311).

Miller (1956) surveyed learning situations involving a range of stimulus-types and found that immediate memory has a general capacity of 7, plus-or-minus 2, chunks. Each chunk of information contains several “bits” of information. The capacity in immediate memory for 7 chunks appears to be relatively stable regardless of how many information-bits are contained within each information-chunk. Thus, memory capacity is increased by a strategy which involves recoding stimuli into fewer and fewer chunks, with more and more information-bits in each chunk.

Similarly, Tulving (1966) argued that the increase in amount recalled over successive free recall trials is a result of increasing the size of the S–units. This organisation benefits memory since a group of items is recalled all together as one, in a “higher-order memory unit”, rather than each item having to be recalled separately.

This creates a memory hierarchy with higher-order units containing lower-order members. Subjects impose this hierarchical structure onto the items-to-be-learned as a strategy to assist learning and recall (Bower et al., 1969a; Tulving and Pearlstone, 1966). Mandler (1967) proposed additional levels of hierarchical organisation through an “extension of Miller’s unitization hypothesis” (p. 332) in which the information-chunks themselves are recoded into even higher-order “superchunks”. A hierarchical arrangement is proposed of high-order chunks or units containing many lower-order chunks which in turn contain many information-bits. This makes it theoretically possible to increase memory capacity indefinitely (Bower et al., 1969b; Ericsson et al., 1980). Mandler explains:

A hierarchical system recodes the input into chunks with a limited set of [7 plus-or-minus 2] items per chunk and then goes on to the next level of organization, where the first-order chunks are recoded into “superchunks,” with the same limit applying to this level, and so forth. The only limit [for the capacity of memory], then, appears to be the number of levels the system can handle. (Mandler, 1967, p. 332)

IVB.51c Typical Effects Accompanying Subjective Organisation.

Several learning and recall effects have been identified which are correlated with subjective organisation. These indicate the importance of categorical organisation within learning and memory: 1) The amount of subjective organisation is positively correlated with the amount of items recalled (Bousfield et al., 1964; Hyde and Jenkins, 1969; 1973; Puff et al., 1977; Tulving, 1962; Thompson et al., 1972). Sometimes this correlation does not occur if there is only a slight relationship between the members of the categories (“weak” categories) (Puff, 1970; Puff et al., 1977). 2) Pre–organised lists of items-to-be-learned are easier to learn than disorganised lists (Bower et al., 1969a; Bower and Clark-Meyers, 1980; Broadbent et al., 1978; Puff, 1970; Tulving and Patterson, 1968). 3) The amount recalled is higher for lists of items which can be readily clustered into obvious categories than for lists of items not containing any obvious categories (Deese, 1959; Tulving and Patterson, 1968). 4) When Subjects are forced to adopt a different organisation, or are prevented from utilising their own preferred subjective organisation, then the quantity recalled decreases (Bower, 1970c; Bower et al., 1969b; Mandler and Pearlstone, 1966; Tulving, 1966). 5) Recall and subjective organisation are higher when Subjects are specifically instructed to categorise the items (Mandler and Pearlstone, 1966), to judge the items in such a way that requires their categorisation (Hyde and Jenkins, 1969; 1973; Johnston and Jenkins, 1971; Mandler and Lewis, 1984), or if Subjects are cued with the category names (Tulving and Pearlstone, 1966). 6) Clusters are also revealed by the timing of responses. Items within the same cluster are recalled in rapid succession, there is then a short pause before another cluster of items is recalled in rapid succession (Mclean and Gregg, 1967; Reitman and Rueter, 1980).

IVB.51d Measurement of Subjective Organisation.

Initial measurements of the amount of clustering were based on Experimenters’ foreknowledge about the categories which were available within the stimulus list. It was simply observed how may items belonging to the same (predetermined) category had been clustered together in Subjects’ recall orders. However, subjective organisation was also found to occur when the group of items did not obviously belong to any categories, but appeared to be “unrelated” (Bousfield et al., 1964; Tulving, 1962). Therefore, researchers developed methods to quantify the amount of subjective organisation regardless of whether obvious categories were available in the stimulus list.

Tulving’s (1962) statistical measurement of subjective organisation (SO measure) was based on the “sequential redundancy” (p. 345) which refers to the frequency with which items appear in the same adjacent order in consecutive recall trials. When the items to be remembered are presented to Subjects in a different random order for each of several learning trials (ie. an absence of sequential redundancy), the subjective organisation of the items is evidenced when the Subject recalls the items in a consistent order across several recall trials (ie. exhibiting sequential redundancy). The amount of subjective organisation across successive recall trials can be represented by the ratio of the obtained redundancy to the maximum possible redundancy.

The problem with the SO measure is that it does not include any correction for the amount of organisation which might be expected to occur by chance. A modified form of the SO measure was developed which also included a computation of “chance”. This was termed “intertrial repetition” (ITR) (A. K. Bousfield and Bousfield, 1966; W. A. Bousfield et al., 1964). The “observed intertrial repetition” [O(ITR)] refers to the frequency with which two items are recalled in the same adjacent order on two consecutive recall trials. The “expected intertrial repetition” [E(ITR)] (ie. chance) is computed based on all the different possible random recall protocols. The total measurement of subjective organisation is then computed by subtracting E(ITR) from O(ITR). Anderson and Watts (1969) expanded this ITR measure to include ITRs recalled in the same adjacent order (unidirectional) and also ITRs recalled in the reverse adjacent order (bidirectional).

Another method was devised which uses an algorithm to determine the set of clusters for each Subject and represents these in a hierarchy referred to as an “ordered tree”. This ordered tree graphically displays the cognitive structuring of the information (Mckeithen et al., 1981; Reitman and Rueter, 1980). This technique has also been modified to simply provide Subjects with a group of items and require that they be arranged into a linear series (rather than requiring the items to be recalled from memory). This creates less demand on the recall of the items and more reliance on the perceived relationships between the items (Naveh-Benjamin et al., 1986).

Sternberg and Tulving (1977) assessed many measures of subjective organisation and found that a form of bidirectional ITR was statistically superior to other measures. They referred to this bidirectional ITR as “pair frequency” (PF). This is the measure selected for use in the experiment presented here. The equation for computing PF is as follows (Sternberg and Tulving, 1977, p. 543):

|

|

|

|

O(ITR): |

Observed intertrial repetition: The number of pairs-of-items recalled in two consecutive recall trials in either the same, or reverse, order. |

|

E(ITR): |

Expected intertrial repetition: The number of O(ITR)s which can be expected to occur by chance. |

|

The formula for E(ITR) is as follows: |

|

|

h = |

number of items recalled in one recall trial (ie. trial t). |

IVB.52 Prototypical Members of Subjective Categories.

Repeated groupings of items in Subjects’ recall orders is indicative of the different categories which Subjects are implicitly using in their cognitive processes. That is, items within the same category are recalled together before moving on to items within a different category.

The order in which items are recalled can also be indicative of the relationship between items within the same category. Research on prototypical members of categories has demonstrated that items which are prototypical members of a category will be recalled before items which are less prototypical of that category (Battig and Montague, 1969; Bousfield and Sedgewick, 1944; Palmer et al., 1981; Rosch et al., 1976). These results have been used to infer that categories are economically represented in memory as prototypes and variations of the prototype (some of this has been considered in sections IVA.30, IVA.111).

Repeated clusters of items in free recall can be indicative of different subjective categories. The order of recall within clusters can be indicative of prototypical and less prototypical members within the same subjective category.

IVB.53 Paradigm for Kinesthetic Spatial Cognition Research.

The occurrence of subjective organisation suggests an overall framework through which to probe the cognitive structure of kinesthetic memory. The experimental task can consist of the learning and free recall of kinesthetic-items (analogous to verbal items). Recall orders can be examined for subjective organisation which would indicate the presence (if any) of kinesthetic categories which are implicitly used during the cognitive process. If clusters are identified then the recall orders within each cluster can be examined for evidence of prototypical members within the particular category. In this initial research the vast number of variable attributes possible within kinesthetic-items was made more manageable by delimiting the stimuli to only kinesthetic spatial (ie. “kinespheric”) items.

This type of research can be used to evaluate whether kinespheric categories outlined within choreutics (or any other system of movement taxonomy) have any resemblance to the kinespheric categories which are actually used during cognition. In specific, the experiment presented here addresses the question:of whether kinespheric categories outlined in choreutics have any psychological validity.

This type of research can also contribute to the schema theory for motor learning (see IVB.11) in which a fundamental problem has been identified as the lack of criteria for distinguishing between different classes or categories of body movement. Kinespheric categories used in the mental representation of bodily movement can begin to be deciphered by identifying the subjective organisation in their free recall.

It is important for this research paradigm that body movements are maintained as discrete items (ie. not connected together into a series of movements). Movements are often learned in a sequence with one movement leading without a pause into the next. This may tend to create an event-like, sequential memory organisation even though the individual kinespheric-items may belong to several different general classes of movement.

This sequential organisation was evident in a preliminary experiment where Subjects were asked to freely recall any movements that they already know. Despite a requirement to segregate movements into discrete items (by saying “here’s one”, “here’s another” etc.) Subjects persisted in producing sequences of movement-items, beginning each movement where the last ended. Subjects often required extra clarification and prompting to segregate movements into discrete items rather than presenting ongoing sequences and Subjects differed widely in how much movement would be included within “one item”. Clearly distinguishing between separate movement-items is not a typical task. The spontaneous tendency is to recall movements as sequences.

At a finer level each movement-item itself has a sequential structure, a beginning, middle, and end. A problem for kinesthetic spatial cognition research is to distinguish what comprises “one movement”. According to the mass-spring and trajectory formation models the elemental movement-unit would consist of a single “stroke” or single phase whereby a skeletal linkage moves from one position to another position defined by a new agonist/antagonist equilibrium point (see IIIB.20). However this is not necessarily how “one movement” is conceived in cognition. For example, cognitive structures have been identified in which a single “unit of motion” in dance is conceived as a sequence beginning at a stable position, progressing through a more unstable position, and ending at another stable position (Lasher, 1981, p. 394).

Clearly the sequential organisation of kinesthetic knowledge is a major aspect of kinesthetic spatial cognition, but this is not the focus of this research paradigm. It is also clear that movements exhibit a discrete cognitive representation. This is evidenced by the ability to deconstruct movement sequences into individual items, rearrange the individual items, and reconstruct the items into new sequences. This type of manipulation is common in dance practice and choreographic methods (Blom and Chaplin, 1982).

IVB.54 Method.

IVB.54a Subjects.

Subjects were 12 students and faculty at the Laban Centre, London (3 men, 9 women) who took part in the experiment voluntarily at the Experimenter’s request.

IVB.54b Materials.

Experimental sessions took place in a large room. Subjects were standing during learning and viewed the kinespheric-items on a video monitor at approximately chest height. There was enough space around the Subject so that kinespheric-items could be physically rehearsed. The volume on the monitor was turned to “off”. During recall Subjects were video-taped by a camera next to the wall of the room. The viewing angle of the camera was marked on the floor and Subjects were free to move within this area.

IVB.54c Stimuli: Kinespheric-items.

A preliminary experiment in which Subjects freely recalled any movements which they already knew revealed that kinesthetic-items may vary along several different attributes simultaneously. For example, a group of movements may vary according to the body-parts used, the direction of motion of the centre of gravity, the type of “action” (eg. turning, jumping, traveling, balancing, gesturing), the dynamic (eg. forceful, delicate, rapid, lingering), the rhythmic pattern, the form of the pose, or the form of the pathway. It is possible that movements may be subjectively categorised according to any of these kinesthetic attributes.

The purpose of this experiment was to asses whether categories of kinespheric form such as those presented in choreutics have any psychological validity. Therefore kinespheric-items were selected which differed along spatial attributes of form and orientation. All other kinesthetic attributes were equivalent (as much as possible) for all items.

The geometrical nature of the forms designated in choreutics may also make them ideal for experimental stimuli since they are abstract and unfamiliar. If well known movements were used (eg. from a particular dance technique, martial arts, sport, or physical labor occupation) then these may be organised according to meaningful associations with their respective well-known movement styles. In contrast to this, the choreutic forms are abstract geometric patterns which are not typically associated with familiar movements and so these kinespheric-items might draw on fundamental cognitive criteria for categorisation rather than already formed semantic associations. Furthermore, the geometric structure of the choreutic forms has been systematically developed (Preston-Dunlop, 1984) and so provides a large set of potential kinespheric stimuli which can be modified and varied along well defined attributes. Therefore, choreutic forms may be an ideal source of stimuli for probing the fundamental structure of kinespheric categories.

A preliminary test indicated that 16 items were enough to present Subjects with a challenge, yet was not so difficult as to be overwhelming. A group of 16 kinespheric-items were selected which varied according to their form (linear reversal, zig-zag, cycle, wave, figure-8) and their orientation (dimensional, Cartesian plane, or diagonal inclination). Briefly, the forms and orientations of the sixteen kinespheric-items were as follows (for Labanotation see Fig. IVB-11; Appendix XVII.20):

|

Number |

Form | Orientation |

| #1. | linear reversal; | 3D pure |

| #2. | zig-zag; | 3D irregular |

| #3. | 4-part cycle; | 3D irregular |

| #4. | linear reversal; | 3D pure |

| #5. | zig-zag; | 3D irregular |

| #6. | 4-part cycle; | 3D irregular |

| #7. | linear reversal; | 1D |

| #8. | linear reversal; | 2D |

| #9. | 4-part cycle; | 2D |

| #10. | plastic wave; | 3D irregular |

| #11. | Large figure-8; | 3D irregular |

| #12. | large 3-part cycle; | 3D irregular |

| #13. | small 3-part cycle; | 3D irregular |

| #14. | large 3-part cycle; | 3D irregular |

| #15. | small 3-part cycle; | 3D irregular |

| #16. | small figure-8; | 3D irregular |

These kinespheric-items were selected to allow for different possible categorisations according to orientation or according to form. For example, would a linear reversal, a zig-zag (from an “axis scale”), and a 4-part cycle elongated along that same axis, be grouped according to their similar orientation? (items #1, #2, #3). Or would the linear reversals (items #1, #4, #7, #8) and the zig-zags (items #2, #5) be grouped together according to their similar form?

All items were virtually identical on other attributes. The starting position was standing, arms down to the side and legs slightly apart. The body-part usage consisted of the right-arm following the pathway with the rest of the body spontaneously accommodating and responding to the motion of the right-arm. The timing of each item was distributed evenly over 6 seconds (see below). The dynamic quality was unaccented neutral dynamics. The costume and setting of the demonstrator was black pants and black shirt against a light-blue background.

|

Figure IVB-11. Forms and orientations of the sixteen kinespheric-items. |

The “actions” (as defined by Preston-Dunlop, 1979, p. 42; 1980, p. 53; Hutchinson-Guest, 1983, pp. xxiii-xxiv) of each kinespheric-item consisted of a “stillness” on counts 1 and 6 and a “transfer-of-weight” on counts 2, 3, 4, and 5. The actions of “condensing”, “expanding”, “twisting”, and “balancing” varied for each of the items depending on what was required by the different pathways. The actions of “turning”, “falling”, “traveling” and “jumping” were not present in any of the items. Body poses were also not controlled (except for the starting position) and these varied according to what was required to fulfill the pathway.

IVB.54d Video tape of the kinespheric-items.

A dancer was video-taped demonstrating the kinespheric-items. He was viewed from the back (ie. facing away from the camera) so that there would be no requirement for Subjects to mentally rotate the movement during learning. This also eliminated any facial characteristics which might inadvertently serve as memory cues.

The demonstrator was guided by a metronome which sounded once each second. Each kinespheric-item lasted for 6 seconds and consisted of the following:

| second 1: | The demonstrator was pictured in stillness in a neutral position, standing with arms down to the side and legs slightly apart. |

|

seconds 2-5: |

The demonstrator performed the movement pathway. |

|

second 6: |

The demonstrator held the last position in stillness. |

The video-taped kinespheric-items were edited into five different random learning sequences with the constraints that two items never occurred in the same adjacent order more than once and no item ever occurred as the very first or the very last item in the sequence more than once (see Appendix XVII.30).

As discussed above, the kinespheric-items were abstract and were not recognisable as any well known movement pattern. Consequently, in pre-experimental trials Subjects reported great difficulty in quickly learning the unfamiliar movements. Therefore, each item was presented three-times in a row to give Subjects longer encoding time and to decrease the anxiety which often occurred since Subjects could not stop the video tape or ask to see a particular movement again. The series of kinespheric-items was edited into the following sequence:

| 2 seconds: | A grid of white squares on a black background was presented to alert the Subject that a new item was about to be presented. |

|

6 seconds: |

The first presentation of the kinespheric-item. |

|

6 seconds: |

The second presentation of the same kinespheric-item. |

|

6 seconds: |

The third presentation of the same kinespheric-item. |

This sequence was repeated 16 times (for the 16 items). After the last item had finished the grid appeared on the screen three times (2 seconds each time separated by 2 seconds of blackness) to indicate that the learning sequence was over. Thus, the entire learning sequence lasted for approximately 5.5 minutes.

IVB.55 Procedure.

Subjects were scheduled for an individual experimental session depending on convenient availability times. Subjects were told only that this was an experiment on “movement memory”.

On arrival, Subjects were given written general information about the experiment and instructions (see Appendix XVII.10). The instructions included: “You will be required to learn 16 different body-movements.” “Please physically perform the movements along with the video tape.” “Please do not make a continuous sequence by joining all the movements together.” “You can recall the movements in any order in which you remember them.” Subjects were allowed to ask questions until the task was understood.

To aid in maintaining the separateness of each kinespheric-item, Subjects were instructed to follow the following procedure during recall:

1) Think of the movement;

2) Say “Here’s one” (or anything similar to this);

3) Demonstrate the movement.

Continue 1), 2), 3), etc.

Subjects were then acquainted with the procedure by learning three practice movements from a video tape of three kinespheric-items (recorded exactly like the experimental items). The Experimenter observed each Subject rehearsing and then recalling the three practice items. All Subjects were able to successfully accomplish this. These three practice items were not used again in the experiment.

When the Subject indicated that she was ready to proceed with each learning trial the Experimenter started the video player and then left the room. The Subject was in the room alone during the learning trial. When the video tape had finished the Subject knocked on the door, the Experimenter entered, turned off the video player and pushed it to the side of the room.

Each recall trial followed immediately. The Subject recalled the kinespheric-items at the same place in the room, and facing the same direction, as she had been during the learning trials. When she indicated that she was ready the Experimenter started the video-camera and left the room. The recall trials ended in one of two ways: 1) When the Subject had recalled all the movements that could be remembered then she knocked on the door and the Experimenter would enter and turn off the video-camera; or 2) After four minutes had past the Experimenter would enter the room, tell the Subject to stop, and turn off the video-camera. The next learning trial would then begin immediately.

Each Subject had five learning trials alternating with five recall trials. The five random sequences of the 16 items were presented in a different order to each Subject. Subjects were given no knowledge of their results after each recall trial but proceeded immediately on to the next learning trial. After the fifth recall trial the Subject was congratulated and the experimental session ended.

IVB.56 Results.

The video tapes of Subjects’ recall trials were observed and (following Sternberg and Tulving, 1977 [see above]) the number of recalled items, observed intertrial repetitions [O(ITR)s], expected intertrial repetitions [E(ITR)s], and pair frequency (PF) was calculated for each recall trial of each Subject (see Appendix XVII.40).

|

Mean Recalls (S.D.) |

4.42 (1.83) |

7.42 (2.64) |

9.83 (3.16) |

11.00 (5.27) |

12.17 (2.59) |

|

Mean O(ITR)s (S.D.) |

|

0.58 |

1.08 (1.00) |

1.67 (2.06) |

2.58 (2.15) |

|

Mean E(ITR)s (S.D.) |

|

0.33 |

0.80 (0.35) |

1.09 (0.35) |

1.16 (0.34) |

|

Mean PF (S.D.) |

|

0.26 |

0.29 (0.87) |

0.58 (1.85) |

1.42 (1.95) |

| Recall Trials: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table IV-11. Performance measures: |

|||||

| NOTE: Data for O(ITR)s, E(ITR)s and PF for the 2nd recall trial refers to the repetitions of S-units from the 1st-to-2nd trials, data for the 3rd trial refers to repetitions from the 2nd-to-3rd trials, etc. | |||||

IVB.56a Number of recalled items.

The mean number of recalled items (12 Subjects, 16 items) for recall trials 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 were 4.42, 7.42, 9.83, 11.0, and 12.17 respectively (see Table IV-11). Paired sample t-tests showed this increase to be significant across the 1st-to-2nd trials (t=5.2, p<.0001), 2nd-to-3rd trials (t=5.16, p<.0001), and the 4th-to-5th trials (t=3.39, p<.006). Only the increase across the 3rd-to-4th trials failed to reach significance (t=1.9, p<.08, n.s.).

IVB.56b Observed and expected intertrial repetitions.

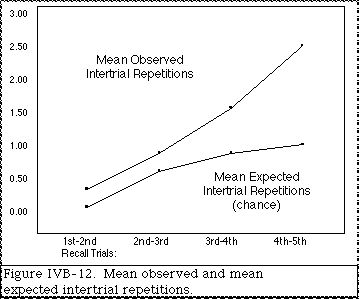

The number of mean O(ITR)s for the 1st-to-2nd, 2nd-to-3rd, 3rd-to-4th, and 4th–to–5th trials were 0.58, 1.08, 1.67, and 2.58 respectively. The number of mean E(ITR)s (ie. chance) for the 1st-2nd, 2nd-3rd, 3rd-4th, and 4th-5th trials were 0.33, 0.80, 1.09, and 1.16 respectively (see Table IV-11).

A multi-subject analysis of variance was carried out. The first factor was intertrial repetitions (ITRs) with two levels (observed and expected), and the second factor was recall performance across consecutive recall trials which had four levels (1st-2nd trials, 2nd-3rd trials, 3rd-4th trials, and 4th-5th trials). Results of the ANOVA showed that the main effect of the first factor (ITRs) was marginally significant, which indicates that observed (ITR)s were significantly more frequent than expected (ITR)s (F 1/11 = 4.22, p<.06). The second factor of recall performance across consecutive trials was highly significant (F 3/33 = 11.29, p<.0001). This indicates that the number of ITRs significantly increased over the five recall trials. The interaction between the performance across trials and the pattern of O(ITR)s and E(ITR)s was also significant (F 3/33 = 2.79, p<.05). This shows that as trials continued, the difference between O(ITR)s and E(ITR)s significantly increased (see Fig. IVB–12).

IVB.56c Pair frequency.

To look more closely at this interaction, paired frequency (PF) across trials was calculated by subtracting E(ITR)s from O(ITR)s. This is therefore a measure of the ITRs which are not expected by chance (Sternberg and Tulving, 1977). Mean PF for the 1st-to-2nd, 2nd-to-3rd, 3rd-to-4th, and 4th-to-5th recall trials were 0.26, 0.29, 0.58, and 1.42 respectively (see Table IV-11). Paired sample t-tests showed that the PF scores across the 1st-to-2nd and the 2nd-to-3rd trials significantly increased to the PF score across the 4th-to-5th trials (t=2.95, p<.01). This reaffirms that subjective organisation is occurring during kinesthetic recall and also confirms that the amount of organisation increases with additional recall trials.

IVB.57 Characteristics of Subjective-units.

Since the occurrence and increase in the subjective organisation of kinespheric-items was verified, the next step was to analyse the composition of subjective-units (S-units) to identify observable criteria (if any) for this clustering. Each of the 16 kinespheric-items exhibits a particular pathway and orientation. These form and orientation attributes were used to analyse the contents of S-units in an effort to determine if they are related to how the item is subjectively organised.

IVB.57a Survey of S-unit occurrences.

A total of 37 different S-units occurred in Subjects’ recall orders (see Appendix XVII.50). Some S-units occurred in as many as 11 ITRs produced by five different Subjects while others occurred in only 1 ITR produced by only one Subject. All S-units produced by at least two Subjects were considered to be the strongest S-units occurring in this experiment and were selected for further analysis. Intertrial repetitions are defined for statistical purposes as repetitions across consecutive recall trials, but if a well established S-unit is repeated in non-consecutive recall trials there is no reason to believe that these non-consecutive ITRs are not also indicative of memory organisation. To provide more data for analysis these non-consecutive ITRs are also included with the occurrences of consecutive ITRs (see Table IV–12).

A descriptive analysis of the form and orientation of the two items within each of the 12 strongest S-units was conducted (for details see Appendix XVII.60). It was found that 63% of the S-units contained two items with similar forms whereas 31% of the S-units contained two items with similar orientations. All of the 12 S–units were not equally robust since some occurred more than others. To correct for the unequal strength of different S–units the number of ITRs for the entire set of 12 S-units were considered as a whole. Of the total number of 47 ITRs, 76% contained two items with similar forms whereas 34% contained two items with similar orientations.

|

S-unit |

#Os |

#ITRs |

Specific Occurrences |

| 1/7 | 4 | 2 | A1-A2 L4-L5 |

| 2/5 | 9 | 6 | B3-B4-B5 D3-D4-D5 E3-E4-E5 |

| 3/14 | 6 | 3 | E4-E5 F3;F5 H2-H3 |

| 4/8 | 7 | 4 | B4-B5 E3-E4-E5 I3;I5 |

| 5/8 | 4 | 2 | B2-B3 H4-H5 |

| 5/14 | 4 | 2 | I4-I5 L4-L5 |

| 5/15 | 4 | 2 | B4-B5 L1-L2 |

| 6/9 | 18 | 12 | B1-B2-B3-B4-B5 E2-E3-E4-E5 F4-F5 G3-G4 I3;I5 L3–L4–L5 |

| 7/13 | 7 | 4 | B2-B3 E1–E2;E5 L2-L3 |

| 9/11 | 7 | 4 | A2-A3 D3-D4-D5 H1;H5 |

| 9/15 | 4 | 2 | D2-D3 E3-E4 |

| 13/15 | 6 | 4 | A3-A4-A5 E3-E4-E5 |

| Table IV-12. Frequency of occurrence for each of the 12 strongest S-units (non-consecutive ITRs included). | |||

|

ABBREVIATIONS: S-units are abbreviated by the numbers of the two component kinespheric-items (see Fig. IVB-11). For easy indexing the lower number is always listed first but it is understood that either item might be recalled first. Total #0s refers to the number of occurrences of the kinespheric-item within the S-unit. Total #ITRs refers to the number of intertrial repetitions of the S-unit. Specific occurrences of S-units are abbreviated by a letter representing each subject, followed by the number of the recall trial (eg. B4 refers to the 4th recall trial of subject B, etc.). Consecutive ITRs are represented by a dash (-) and non-consecutive ITRs are represented with a semi-colon (;) |

|||

This analysis reveals that form attributes are greater descriptors of kinespheric clustering than orientation attributes. This indicates that the composition of kinespheric categories is determined more by the forms of items than by their orientation.

IVB.57b Directionality of S-units.

The two items within an S-unit can be recalled with either item first, this is referred to as the “directionality” (Anderson and Watts, 1969; Sternberg and Tulving, 1977). An S-unit’s directionality can be an indicator of category prototypicality since prototypical category members tend to be recalled before members which are less prototypical of the category (Battig and Montague, 1969; Bousfield and Sedgewick, 1944; Palmer et al., 1981; Rosch et al., 1976). Another question is whether attributes of form or orientation describe S-unit directionality.

Five of the 12 strongest S-units were identified as being primarily unidirectional (see Appendix XVII.70). Three rules were derived which describe their pattern of directionality: 1) Small kinespheric-items are recalled before larger items (S-units 5/15 and 9/15); 2) If both items are small the higher item is recalled first (S-unit 13/15); 3) One-dimensional oriented items are recalled first, two-dimensional items are recalled second, and three-dimensional oriented items are recalled last. This last rule conforms to the prototype/deflection hypothesis (see IVA) and describes the uni–directionality of S-units 4/8 and 6/9 and also describes the marginal uni–directionality of the S-units 1/7 and 5/8 (for numbers of kinespheric-items, see Fig. IVB-11).

Several other S-units occurred equally often with either item recalled first (bidirectional). This bidirectionality can also be described by these three rules. For S–units 2/5, 3/14, and 5/14 none of the rules applies and so neither item tended to be recalled first. The bidirectionality of the S-unit 7/13 may result from a conflict between Rule 1 and Rule 3. The bidirectionality of the S-unit 9/11 may occur since item #11 does not have any obvious deflected component, but may instead be remembered as a frontal plane moving around a sagittal axis, thus neutralising the effect of Rule 3.

This description of the components of unidirectional and bidirectional S-units indicates that orientation may play a role in directionality. Dimensional oriented movements tend to be recalled before other orientations. This is in accordance with the prototype/deflection hypothesis (see IVA) which posits that dimensional orientations serve as cognitive prototypes for other orientations within the same kinespheric category.

IVB.57c First and Last recall position ITRs.

Some measures of subjective organisation include the organisation of items which are recalled in the very first or the very last recall position on two consecutive recall trials (Tulving, 1962). In this experiment last-position ITRs did not appear to be an important factor since only two occurred (item #7 for Subject E; item #11 for Subject C) and so were not considered further. However 12 first-position ITRs occurred and so these appeared to be a prominent factor in organisation of recall orders. Items organised into first-position ITRs are referred to here as “first-units” (F–units) (see Appendix XVII.80).

|

Orientation of kinespheric-items |

Number of F-unit occurrences: |

|

1-D: 2-D: 3-D pure: 3-D deflected: |

#7 A1 A2 G2 G3 G4 G5 I2 I3 I5 J3 J4 J5 #8 H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 #9 B1 B2 B4 L1 L2 L3 L5 #1 J1 J2 #4 #2 #3 #5 #6 #10 #11 #12 #13 E3 E4 #14 #15 #16 |

| Table IV-13. Kinespheric-item orientation and number of F-unit occurrences (reversed F/S-units and non-consecutive ITRs included). | |

Out of the 12 F-unit ITRs, 10 of these contained one-dimensional and two-dimensional oriented kinespheric-items (items #7, #8, #9). A closer scrutiny also revealed that in 9 out of the 12 F-unit ITRs it was not a single item which was organised into the first recall position but it was an entire S-unit. That is, if an item was organised into an F-unit it also tended to be organised into an S-unit. These S–units organised into the first recall position are referred to here as “first/subjective-units” (F/S–units) and they appear to be indicative of a higher level of organisation. The only case that this was not true was for item #7 which consisted of a vertically oriented line. It may be that the extreme prototypicality of this item allowed it to be easily organised into an F-unit on its own without the more extensive processing involved in the formation of an S-unit. This is supported by the result that more F-units contained item #7 than any other item.

When an F/S–unit occurred, the same Kinespheric-item did not always occur first. For example, Subject L recalls item #9 first in the F-unit 9/8 for the first two recall trials, then on the third recall trial recalls it (in the opposite order) as 8/9. These both appear to be examples of the same F/S-unit and so reversed F/S-units were also included in the data analysis (see Appendix XVII.90). In addition it was evident that non-consecutive ITRs occurred for well established F-units. When non–consecutive ITRs occurred for a Subject who also produced consecutive ITRs of the F–unit, then these non-consecutive ITRs were included in the data analysis.

A histogram representing the number of times which particular kinespheric-items occurred as F-units reveals that one-dimensional items occurred as F-units most frequently, followed by two-dimensional items less frequently, and three-dimensional items are rarely organised into the first recall position (Table IV-13). This recall of one- and two-dimensional oriented movements in the first recall position supports the prototype/deflection hypothesis (see IVA).

IVB.58 Discussion and Directions for Future Research.

The results of this experiment can be interpreted relative to the structure of kinespheric categories. It was first confirmed that subjective organisation occurred during kinespheric free recall and that this organisation increased significantly across the five recall trials. Since the occurrence of subjective organisation was statistically verified it was then justifiable to analyse the composition of the subjective-units (S-units) and infer the structure of kinespheric categories from these.

In this experiment the composition of S-units was better described by the form of the kinespheric-items rather than by their orientation. This leads to a hypothesis that kinespheric-items with the same form tend to be organised into the same category.

Studies of category prototypes have shown that prototypical members of categories tend to be recalled before less-typical members of the category (Palmer et al., 1981; Rosch et al., 1976; see IVA.32). If this holds true for kinespheric categories then it can be inferred that if one item within an S-unit is more frequently recalled before the other item within the S-unit, that the former item is more typical of the kinespheric category than the latter item.

In this experiment several S-units were identified as unidirectional (ie. one item is usually recalled first). An analysis of the attributes of the firstly recalled items revealed that they were either small forms, or exhibited a one- or two-dimensional orientation. Kinespheric forms with either a one- or two-dimensional orientation were also recalled in the first recall position more often than three-dimensionally oriented forms. These effects associated with the orientation of kinespheric-items leads to the hypothesis that one- and two-dimensional oriented items are perceived to be more prototypical of their categories than three-dimensional oriented items.

Thus, the results of this experiment suggest a twofold hypothesis: Kinespheric categories are distinguished according to the form, and prototypicality within a category is defined by the orientation. This is also in accord with the prototype/deflection hypothesis (see IVA). However, the data presented in this experiment do not give an unequivocal support for this hypothesis. The orientation of the kinespheric form also appeared to contribute towards distinguishing the category, and the size of the form appeared to contribute towards defining the prototypicality. However the twofold form and orientation hypothesis derived here provides a starting place for future experiments.

In the current experiment there was no clue whatsoever about the type of kinesthetic clustering which might occur. To reduce the variable kinesthetic attributes which might contribute to clustering the stimuli were limited to kinesthetic spatial, that is “kinespheric”- items. However, even within the restricted range of kinespheric stimuli there are still multiple variables which each may be effecting the results. For example, many of the kinespheric-items were extremely complex in which several orientations occurred during a single pathway. In these cases it was impossible to determine which orientations the Subject was using for categorisation. The size of the form also appears to effect how it is encoded and categorised. In addition, clustering will always be relative to the contents of a particular stimulus list. That is, the items may be clustered in one way within one stimulus list but clustered in another way within a different stimulus list.

What is necessary in future research is to drastically isolate kinesthetic attributes so that their cognitive significance can be assessed independently. Stimuli lists need to be composed of items which differ from each other along one or two controlled attributes which are being tested one at a time, rather than having multiple attributes varying from item to item. The twofold form and orientation hypothesis for kinespheric categories and prototypes derived from the results of this experiment gives a potential starting place for creating stimuli lists.

This experiment has shown that the paradigm of subjective organisation in kinesthetic recall produces an abundance of data and so can be a valuable method through which to probe the structure of the mental representations of kinesthetic knowledge.

IVB.59 Summary: Subjective Organisation in Kinesthetic Recall.

A movement memory experiment was devised with the purpose of identifying whether categories of kinesthetic spatial information are actually used in cognitive processes. Subjects learned sixteen discrete kinespheric-items and were allowed to recall these in any order over five learning and free recall trials. Measurements of “subjective organisation” indicated that kinespheric-items were organised into categories during learning and recall. An analysis of the categories led to a twofold hypothesis of category membership defined by the form (ie. movements with the same form were clustered together regardless of their orientation) and category prototypicality defined by the orientation (ie. movements oriented along a pure dimension or a Cartesian plane were recalled at the beginning of a cluster). Identifying kinesthetic spatial categories in this way has not been heretofore undertaken in psychological research and so constitutes additional new knowledge.