An experiment was designed as a test of the prototype/deflection hypothesis which posits that dimensional and diagonal directions serve as conceptual prototypes while actual body movements occur as deflected directions (“inclinations”). This suggests that deflected directions may be represented in memory according to their relationship to the more easily imaged reference points of the dimensional and diagonal directions. Psychological research has found evidence for the use of cognitive reference points in tasks involving colours, line orientations, numbers (Rosch, 1975a), and geographical locations within a city or a university campus (Sadalla et al., 1980). The purpose of this experiment was to address the question of whether cognitive reference points are also used in the mental representation of the kinesphere.

IVA.111 Reference Points.

Wertheimer (1923, p. 79) suggested that certain stimuli which display a high degree of the Gestalt “pragnanz” (see IVB.27) serve as ideal types, and that other less ideal stimuli are perceived and remembered according to their relationship to the ideal types. Rosch (1975a) referred to this notion of ideal stimuli as “cognitive reference points” which are stimuli within a category that other stimuli within the same category are seen “‘in relation to’” (p. 532), and speculated that prototypical members of categories might serve as reference points for other less prototypical members of the category. Rosch designed two experimental tasks in order to test whether stimuli in a category are conceived “in relation to” a prototypical reference stimulus.

The first task involved “linguistic hedges” which are used in language to express metaphorical distance between concepts. Hedges were arranged into sentence frames each containing two blank spaces (for example):

“___ is essentially ___”; “___is basically ___”;

“___ is roughly ___”; “___ is almost ___”;

“___ is sort of ___”; “Loosely speaking ___ is ___”.

Subjects were presented with pairs of stimuli in the same category (ie. colours, numbers, line orientations) and their task was to place the two stimuli into the two blanks in the order that the sentence seemed to be most true or make the most sense. The hypothesis was that prototypes (reference stimuli) should be more often placed in the second blank and deviations (non-reference stimuli) should be more often placed in the first blank. For example, the sentence “996 is essentially 1000” seems to make more sense than “1000 is essentially 996”, thus indicating that the number 1000 serves as a cognitive reference point for the number 996.

In the second experiment Rosch (1975a) used a semi-circular grid in which one stimulus was fixed at the origin of the grid and the Subject’s task was to physically place the other stimulus at a location within the grid which best represents the perceived similarity or difference (ie. “psychological distance”) between the two stimuli. The hypothesis was that non-prototypes are conceived to be closer to a prototype than vice versa. Therefore, when a prototype is fixed at the origin of the grid the non-prototype should be placed closer to it than vice versa.

The results for both experiments supported the hypothesis that prototypical colours (determined in previous research by Berlin and Kay, 1969 and Rosch-Heider, 1972); vertical and horizontal oriented lines (and planar-diagonals in the verbal hedges task); and numbers of multiples of 10; served as reference points for other less prototypical members of their respective categories.

Sadalla and Colleagues (1980) used these same experimental tasks to probe whether reference points are also used in memory for locations in a city or in a University campus. They reiterate the assumptions implicit in the concept of a spatial reference point:

. . . the position of a large set of (nonreference) locations in a particular region is defined in terms of the position of a smaller set of reference locations. . . .

. . . the location of different places within a region is known with different degrees of certainty. Reference points are those places whose locations are relatively better known and that serve to define the location of adjacent [non-reference] points.

. . . [Thus, in interests of cognitive economy] the relationship between reference points may be [explicitly] stored and the position of other points computed from the knowledge that they are proximate to specific spatial reference points. (Sadalla et al., 1980, pp. 516-517)

Reference points are the prototypical spatial locations. Other loci are derivatives of these prototypes. The derivatives are more apt to be conceived “‘in spatial relation to’” a reference point than vice versa. This leads to the “asymmetry hypothesis” which posits that “Adjacent places should be judged closer to reference points than are reference points to adjacent places” (Sadalla et al., 1980, p. 517).

Following Rosch (1975a), Sadalla and Colleagues (1980) used both the linguistic hedges task and the grid-placement task. Locations within a University campus and within a large city were used as stimuli. Both experiments supported the hypothesis that certain locations were utilised as cognitive reference points for other (nonreference) locations.

These studies suggest an experimental method for testing the choreutic prototype/deflection hypothesis. According to this hypothesis the orientation of bodily movements is conceived according to pure dimensions, diagonals and Cartesian planes, but actually executed along deflected “inclinations”. If this is so, then evidence should be able to be found that dimensional and diagonal directions serve as reference points for other directions.

IVA.112 Labanotation Direction Symbols as Kinespheric Stimuli.

In the experiment presented here Labanotation direction symbols (see IVA.13) were used as stimuli in the grid task developed by Rosch (1975a) in an attempt to assess if reference points are used within the cognitive representation of the kinesphere. The direction symbols were chosen for stimuli because each symbol presents relatively the same amount of information. This is not true in the case of words where diagonal directions are specified by a conjunction of three dimensional words. Therefore words may not be adequate stimuli since they introduce verbal cognitive structures rather than cognising about kinesthetic spatial representations. Indeed, because of the pictorial design of the Labanotation direction symbols it may be that experienced readers translate directly from the symbol into kinesthetic spatial information without any intermediary verbal stage.

Labanotation direction symbols are certainly initially learned and orally discussed according to their verbal labels. Thus it is probable that the verbal labels are always associated with direction symbols. The question remains as to whether an experienced reader recalls the verbal labels when reading a direction symbol if the task does not induce it. It was assumed for this study that Subjects with previous experience reading and writing Labanotation direction symbols would translate these directly into kinesthetic spatial information in the grid-task. However the linguistic hedges sentence-completion task was not used because this task appears to encourage the translation of direction symbols into words rather than images of body action.

IVA.113 Method.

IVA.113a Subjects.

Subjects were twelve adults who had previous experience reading and writing body movement with Labanotation direction symbols. Subjects’ experiences ranged from the successful completion of a college-level course in Labanotation and a working knowledge of direction-symbols, to advanced teachers in the field. Subjects took part voluntarily at the Experimenter’s request.

IVA.113b Stimuli.

Labanotation direction symbols.

Pairs of Labanotation direction symbols were selected for use as stimuli. There are symbols for the 27 main directions (1 central, 6 dimensional, 8 diagonal, and 12 diametral directional points; see IVA.13), this yields a total of 351 possible stimulus–pairs. It was estimated that a 15 minute test period would be within Subjects’ attention span, and that ample time for a distance judgment might be 7.5 seconds. This yielded an estimation for a total of 120 distance judgments within the test. Of these, 4 were set aside for “warm-up” judgments, leaving 116 judgments during the actual test. Each stimulus-pair must be judged in each direction (ie. x-y or the reverse direction y-x) so it was estimated that approximately 58 stimulus-pairs could be selected for use in the experiment.

It is probable that non-reference points will be nearby their corresponding reference point. For example, in the kinesphere it can be hypothesised that the left-upward and the right-upward directions are known in relation to the more prototypical dimensional upward direction. Therefore, pairs of direction symbols should be selected which are nearby.

The choreutic system of directions (see IVA.20) distinguishes between dimensional, diagonal, and diametral directions which can each be notated with a single direction symbol. Notation of inclinational directions typically requires two direction symbols so these were not tested.

Pairs of direction symbols were selected which represented different possible pairings of nearby dimensional, diametral, and diagonal directional points. It was predicted that reference point effects would be found in these pairings of nearby directional points so they were considered to be test-pairs. In addition to test-pairs, other pairs of direction symbols were chosen as distractions in which no reference point effects were expected. These consisted of nearby directions of the same type (eg. two dimensional directions, two diametral directions) and also radii and full axes through the kinesphere. A final group of 59 pairs of direction symbols were chosen for use as stimuli (see Appendix XIII.10). These were divided into test-pairs and distractor-pairs and further divided into the specific type of pair:

| Test-pairs: | ||

| Dimensional / Diametral | 16 stimuli-pairs | |

| Dimensional / Diagonal | 10 stimuli-pairs | |

| Diametral / Diagonal | 8 stimuli-pairs | |

| Nearby distractor-pairs: | ||

| Dimensional / Dimensional | 7 stimuli-pairs | |

| Diametral / Diametral | 4 stimuli-pairs | |

| Distant distractor-pairs: | ||

| Radii | 6 stimuli-pairs | |

| Full axes | 8 stimuli-pairs | |

Semi-circular grids.

A 25.25 cm diameter semi-circular grid (47 semi-circular lines) was printed on sheets of A4 paper (29.5 x 21 cm). The sheets were oriented long-side down so that the origin of the grid was at the bottom centre of the page. One direction symbol was printed at the origin of the grid, another direction symbol was printed at the upper-right corner of the sheet (see Appendix XIII.50).

Test books.

Test books were loosely bound and contained 122 pages of grids with direction symbols and 3 pages of task instructions and examples. When the tests were taken the test book was oriented long-side down so that pages turned upwards.

IVA.114 Procedure.

Subjects read the first three pages of the test book which contained one page of instructions, a page consisting of a sample grid and direction symbols, and a page of clarifying information. Subjects asked questions until they understood the task.

The written instructions directed Subjects to “Read the beginning direction from the symbol at the centre of the grid”, “Read the ending direction from the symbol outside of the grid”, and then to “Write the ending direction symbol at a location within the grid which best represents the distance of movement from the beginning direction to the ending direction”. They were then given three examples of different kinespheric distances. Subjects were further instructed to “Proceed through the test booklet one page at a time”, to “Make one distance estimation for each page”, to “proceed as quickly as possible, while still retaining accuracy”, and that “Once you have turned a page, it is finished and you are not allowed to turn back” (see Appendix XIII.40).

Each stimulus-pair was presented twice to each Subject, once with stimulus 1 at the origin of the grid, and once with stimulus 2 at the origin (for test-pairs half of the hypothesised reference-points were labeled stimuli 1, and half were labeled stimuli 2; for distractor-pairs the stimuli were arbitrarily labeled stimulus 1 or 2). Stimulus-pairs were randomly ordered with the constraint that no similar combination of dimensional, diametral, diagonal or central directions occurred within 2 judgments of each other. The stimulus list was presented in one order to half the Subjects, and in the reverse order to the other half of the Subjects (see Appendix XIII.20-.30).

Four other stimuli-pairs (exemplifying of a variety of kinespheric distances) were presented at the beginning of all Subjects’ tests as a warm-up. These were presented in two different random orders, each given to half of the Subjects.

IVA.115 Results and Discussion.

Each distance judgment was measured to the nearest millimeter from the centre of the direction symbol printed at the origin of the grid to the centre of the direction symbol drawn by the Subject (see Appendix XIII.60). Each stimulus-pair was considered separately to identify whether an asymmetry in distance judgments had occurred. Therefore a paired grouped t-test (two tailed) was conducted for each of the 59 stimulus-pairs. Because of so many t-tests it is statistically likely that some would be significant just out of chance. A correction is needed to control for this type of error and so a low probability of effects being attributable to chance (p < 0.001) was chosen as the level of significance.

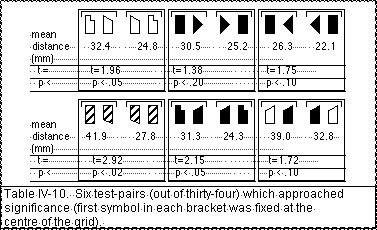

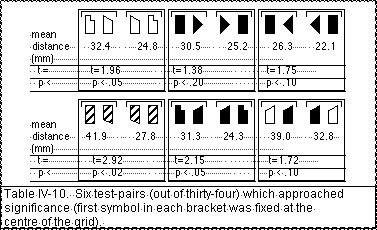

None of the stimulus-pairs reached significance at this level (Appendix XIII.70). Only six (out of thirty-four) of the test-pairs even approached significance (Table IV–10). In three of these when the dimensional direction was at the origin of the grid the judged distance to the diametral direction was larger than vice versa. This is the opposite effect as predicted by the asymmetry hypothesis for dimensional prototypes. For the other three test-pairs which approached significance when the diagonal-locus was at the origin of the grid the judged distance to a dimensional point or a diametral point was smaller than vice versa. This is consistent with the effect as would be predicted by the asymmetry hypothesis for diagonal prototypes, but the size of this effect was too small to reach significance. Therefore the results of this experiment do not support the hypothesis that kinespheric locations are mentally represented according to a set of prototypical reference points.

It may be that cognitive reference-points are used for kinespheric information but that this experiment failed to demonstrate an effect. Several potential problems with the experiment were identified. While Subjects were taking the test it was often observed that they used body movements towards the directions indicated by the direction symbols. Sometimes two body-parts (eg. both arms) reached into both directions simultaneously, at other times a single body-part was moved back and forth between the two directions two or three times. One advanced Subject also reported that she visualised the interval between directions rather than the motion from one direction to another. These attributes indicate the possibility that Subjects were estimating the length of the line between the two directions regardless of which direction was to be considered as the starting point.

Similarly, Subjects with advanced knowledge of Labanotation direction symbols were sometimes overheard making computational judgments about the distance between directions, for example, “45°”, “90°”, “full way” (180° between directions) or “half-way” (90° between directions). This computation would be identical regardless of which direction was considered as the starting point.

It was stressed in the instructions that distance judgments should be made from one direction to another direction. However these observations indicate that Subjects may have been estimating the length of the line or the size of an angle, between two directions regardless of which direction was designated as the starting point. If this is true then placing one direction symbol at the origin of the grid would be inconsequential since Subjects would tend to treat both direction symbols equally.

Other tasks may induce a sequential conception (from one location towards another location). The verbal sentence-completion task using linguistic hedges developed by Rosch (1975a) was ruled out because it may elicit verbal rather than kinesthetic processing of the direction symbols. However this task could indicate if there is an effect of dimensional reference-points for verbal representations of spatial directions. A variation of the sentence-completion task might be to simply present Subjects with two direction symbols and ask that they arrange them into the most logical sequence. Another possibility would be measuring the reaction-time for judgments of the distance or direction between two kinespheric locations. This type of task was used by Sadalla and Colleagues (1980) to identify reference points within the spatial representation of locations in a university campus or in a city. Labanotation direction symbols could be presented one at a time to ensure that the judgment was made from one direction towards the other direction. The representation of a non-reference point implicitly includes the reference point since the non-reference point is hypothesised to be mentally represented “in relation to” the reference point. Therefore a non-reference point would prime the Subject for the reference point, and accordingly, reaction times should be shorter when the non-reference point is presented first.

Recall of kinespheric locations could also be tested by presenting Subjects with body-poses which they are later required to reproduce with their own body. Similar tasks have found a bias toward the planar-diagonal when recalling the location of a dot within a circle (Huttenlocher et al., 1991) or the incidental memory bias toward the horizontal when recalling an arm position (Clark and Burgess, 1984). The hypothesis would posit that the locations of limbs in body-poses would be recalled more similar to prototypical locations than they actually were.

IVA.116 Conclusions: Kinespheric Reference Points.

Subjects were presented with two kinespheric directions (notated with Labanotation symbols). One symbol was drawn in a semi-circular grid at a location which represented its distance from another kinespheric direction. Each stimulus-pair was judged once in each direction (once with stimulus 1 fixed at the origin of the grid, once with stimulus 2 fixed). Distance judgements were not significantly different regardless of which stimulus was fixed at the origin of the grid This did not support the hypothesis of reference points in the mental representation of the kinesphere. However, it appears that Subjects tended to estimate the static length of a line or the size of an angle rather than a distance from one location towards another location. Alternative experiments are suggested.