|

|

Figure IIIB-1. The biceps as a spring supporting the mass of the forearm. |

A variety of spatial cognition and motor control research indicates that the elemental units of spatial information used by the kinesthetic perceptual-motor system are individual locations (rather than distance moved, pathways followed, or particular muscles contracted). This validates Laban’s conception of using individual locations as the basic kinespheric code for limb paths and poses in choreutics and Labanotation, which is virtually identical to the motor control model of “trajectory formation” (see IIIB.30).

Motor memory research often uses spatial positioning tasks in which Subjects grasp the handle of an apparatus which can be moved in a fixed direction along a straight line (linear positioning) or through an arc (angular positioning) (Appendix V).

IIIB.11 Location versus Distance Recall.

Subjects’ ability to recall the end-locus of a positioning apparatus might be based on memory for the limb’s location or on memory for the distance moved from the starting position to the final location. These two possibilities of distance recall or location recall can be experimentally isolated. The learning trial is undertaken normally. At the recall trial the beginning position of the apparatus is changed and the Subject attempts to reproduce either the distance moved, or the location moved to.

It is commonly demonstrated that locations can be recalled more accurately than distances (Kelso, 1977a; Marteniuk, 1973; Marteniuk and Roy, 1972; Posner, 1967; Roy and Kelso, 1977; Roy and Williams, 1979). Recalling the final location from a different starting location is just as accurate as recalling the final location from the same starting location. That is, information about the distance moved does not result in better location recall than when a different distance is moved (Keele and Ells, 1972; Roy, 1977). Thus, the fundamental code for the memory of limb-position appears to be the end-location rather than the distance moved.

These results were extended by Russell (1976) who used a task of moving a hand-held stylus from a starting to an ending locus (the direction of movement was not constrained as it is with a limb-positioning apparatus). One group of Subjects practiced recalling a final locus from a variety of different starting loci. They were then able to recall the final locus from a new (never before experienced) starting locus just as accurately as other Subjects who had repeated practices from this starting locus. Thus, the final location appears to have been encoded in memory rather than the direction or the distance moved.

Some researchers have found that after a retention interval distance recall exhibits a performance decrement while location recall is just as accurate as if recalled immediately. Filling the retention interval with a secondary task (digit computation or a visual-spatial reasoning) results in a performance decrement to locus recall but has no effect on distance recall (Laabs, 1973; Williams et al., 1969). This indicates that location information is mentally rehearsable while distance information is not. That is, the mental rehearsal of locus information causes it to not decay during an unfilled retention interval, but this rehearsal is disrupted by a secondary task during retention. Since distance is not rehearsable it decays an identical amount regardless of whether the retention interval is filled or unfilled. However, other research has demonstrated that recall of location and distance both suffer a performance decrement after an unfilled retention interval and neither suffers any further from a digit classification task during retention (Posner, 1967).

Regardless of rehearsiblity, location recall is always demonstrated to be more accurate overall than distance recall. This can be interpreted as evidence that limb movement is fundamentally encoded as an end-location. This is ecologically advantageous since an invariant end-location can be recalled regardless of variable movements which might be required to arrive at that location.

Distance information may be derived from location information by computing the change-of-stimulation from one position to another. Some researchers (Laabs, 1973; Roy and Williams, 1979, p. 237) suggest a strategy in which the duration of the movement is determined by counting to oneself. When starting at a different beginning locus the distance can be recalled by moving at the same velocity and for the same overall duration (measured by counting).

IIIB.12 Switched-Limbs in Positioning Tasks.

In contrast to the usual “same-limb” recall, Wallace (1977) used a “switched-limb” procedure in which the end-locus of a spatial positioning task is learned with one arm and recalled with the other. This is intended as a test of the “location code” or the “target hypothesis”:

According to the target hypothesis, kinesthetic information about a movement endpoint contacts the perceptual process, which, in turn, converts the actual kinesthetic signals into more abstract information. The location code is represented in memory as a point within the learner’s three dimensional coordinate system. (Wallace, 1977, p. 158).

Similarly, Stelmach and Larish (1980, p. 167) refer to this as the “spatial location code” hypothesis which posits that “spatial localization is made on the basis of an abstract spatial code, rather than on stored proprioceptive information”. If different body-parts can each recall a location equally well, this would indicate that the memory code is more abstract and not based on the actual muscles used.

Wallace (1977) found that an end-locus in a linear positioning task can be recalled equally well with a leftward or a rightward motion of the same arm. However, the location could be accurately recalled with the other switched-arm only in the same direction of motion as it was learned. This provides partial support for an abstract location code.

Larish and Colleagues (1979) found that recalling a location with the same arm was just as accurate as simultaneously matching the location with the other arm, but that recalling the locus later with the other arm was not as accurate. However in this “dual-track apparatus” the two arm-hands were actually recalling two different locations (p. 216) and so it is not directly comparable to Wallace’s (1977) switched-limb task. Nevertheless the accuracy of matching the location with the other arm provides some support for the use of an abstract (body-part free) location code.

In further experiments, same-limb recall of a locus was more accurate than switched-limb recall for long (50-60cm) movements, but that these were equally accurate for shorter movements (Stelmach and Larish, 1980; Larish and Stelmach, 1982). This also provides partial support for the locus code. These researchers hypothesize that the less distant targets may fall within the Subjects egocentric, body-based reference system (see IIIA). However, this explanation appears contrived to fit their results and puts artificial limits on the range of spatial locations which can be mentally represented egocentrically.

A dominate theory of motor control is known as the “mass-spring model” (Jordan and Rosenbaum, 1989, p. 732; Pew and Rosenbaum, 1988, p. 479; Sheridan, 1984, pp. 69-73) or as the “spring hypothesis” (Rothwell, 1987, p. 29) and posits that the muscular-skeletal system is controlled like a system of masses and springs. These are considered analogous to the mass of the limbs and external objects, and the spring-like character of muscles. The mass-spring model provides a theoretical foundation for a location code in movement memory.

|

|

Figure IIIB-1. The biceps as a spring supporting the mass of the forearm. |

IIIB.21 Mass-Spring System.

The simplest mass-spring system consists of a spring attached to a secure fixed support on one end and a free movable mass suspended on the other end (Tuller et al., 1982, p. 266). For example, the spring is analogous to the biceps muscle attached at the fixed end to the shoulder and at the free end supporting the mass of the forearm, hand, and any object held in the hand (Fig. IIIB-1).

A characteristic of springs is that when set in motion they oscillate back and forth until finally coming to rest at an equilibrium point. The same thing occurs if a person attempts to hold their forearm still when it is unexpectedly disturbed by an external force; their forearm will oscillate between lengthening and shortening until returning to the original position. This mimics the behaviour of springs and attests to the elastic characteristic of muscles. Because of this well known elastic property of muscles they are considered as “oscillatory systems” (Tuller et al., 1982, p. 267) and as analogous to springs (Bernstein, 1984, p. 79; Bizzi et al., 1976; Cooke, 1979; 1980; Kelso and Holt, 1980; Nichols and Houk, 1976; Rack and Westbury, 1969).

IIIB.22 Agonist / Antagonist Equilibrium Points.

The mass-spring model posits that static limb positions occur when the resultant forces of agonist and antagonist muscles are in equilibrium. This is known as the “equilibrium point” (Jordan and Rosenbaum, 1989, p. 733, Pew and Rosenbaum, 1988, p. 480; Polit and Bizzi, 1978). When a new equilibrium point is set then the limb will move in the shortest way possible to the new location of agonist/antagonist equilibrium.

Equilibrium points specify positions of the limbs without specifying the movement’s distance or path. This can be referred to as “‘final position control’” (Bizzi and Colleagues, 1982, p. 397; Hogan, 1984, p. 2745) and is synonymous with the concept of a “location code”. The opposing tensions in agonist and antagonist muscles drive the limb towards the equilibrium point in the most direct way possible.

IIIB.23 Equifinality.

The mass spring model predicts that the limb will reach the intended equilibrium point regardless of temporary unexpected perturbations of the moving limb (eg. encountering an obstacle) and unplanned for variability such as joint viscosity, limb inertia, and external obstacles. “Interaction torques” will also be generated in which inertia from one body segment is transferred through a joint into another segment (Bizzi and Mussa-Ivaldi, 1989, p. 775). These have been shown to occur to a significant amount even during arm movements at medium speed and so must be accounted for in the control of movement (Hollerbach and Flash, 1982).

According to the equilibrium point hypothesis the spring-like behaviour of muscles will allow the limb to automatically adjust its path and arrive at the intended destination point without sensory feedback and regardless of these unpredictable physical variables. This is known as the property of “equifinality” (Jordan and Rosenbaum, 1989, p. 733; Kelso and Holt, 1980, p. 1183; Tuller et al., 1982, p. 268). This allows motor actions to automatically adjust to unplanned for variables without having to replan and reinitiate the movement (Berkenblit et al., 1986; Feldman, 1986; Sakitt, 1980; Saltzman and Kelso, 1987).

Equifinality has been demonstrated. Polit and Bizzi (1978; 1979) trained monkeys to point their forearm at a light in exchange for a reward (without sight of the limb). After the onset of the stimulus light (cuing the monkey to move) if the limb was briefly pushed away from its starting position the pointing movement was still just as accurate (even when kinesthetic feedback had been eliminated by surgical means). If the limb was unexpectedly pushed past the target it would reverse its motion and return to the target locus. This same effect occurred when exterior loads were temporarily applied to head movements toward a visual target in both normal and surgically deafferented monkeys (Bizzi et al., 1976; 1978; Cooke, 1979). Brief displacement of the finger also did not effect the finger’s accuracy at achieving the final position for both deafferentiated (Pressure cuff around the wrist) and normal human Subjects (Kelso and Holt, 1980).

If a continuous (rather than temporary) additional force is applied to the limb then a greater force overall will be required to reach the target and so it will be undershot. This is analogous to the different muscular forces required for moving masses at different orientations to gravity. For example, Schmidt and McGown (1980) measured the accuracy in pointing a lever at a target within a particular duration of time (‰0.08-0.09 sec.). The mass of the lever to-be-moved was unexpectedly increased or decreased. When the lever moved in the horizontal plane (thus no additional weight to overcome, only inertia of moving a mass horizontally) the final target was recalled just as accurately but the duration of the movement changed (longer duration for greater mass, shorter duration with less mass). When the lever moved in a medial plane the addition of a mass requires greater overall muscular force to achieve the target position. In this case the target was undershot and the duration showed the same pattern as before. The target was also undershot when an additional continuous force was applied with increased spring tension to a horizontally moving lever. According to the mass-spring model a continuous additional force is compensated for by increasing the overall tension or “stiffness” in all muscles (Cooke, 1980; Tuller et al., 1982, p. 266), however the essential location code of the equilibrium point is unchanged.

IIIB.24 Sensory Feedback Required for Fine Control.

The mass-spring model describes a location code in movement control which is not reliant on kinesthetic feedback for its accurate recall. However, movement which requires fine adjustments and ongoing control will be dependent on feedback. Day and Marsden (1981; 1982) measured the accuracy of pointing to a target by thumb movement (interphalangael flexion). When the friction acting against the thumb’s movement was unexpectedly changed it led to errors in arriving at the target when Subjects did not have guidance from sensory feedback (“digital nerve block” eliminated joint and skin sensations). A case study is also reported about a patient with relatively normal movements but having a lack of sensation below the elbow. Gross forearm/hand movements could be performed well without visual guidance (eg. drawing figures in the air, imitating piano playing, moving to a target), however perturbances of the thumb, and other tasks requiring fine adjustment to environmental stimuli (eg. carrying a cup of water, grasping and writing with a pen) were quite difficult without visual guidance (Day et al., 1981; Rothwell et al., 1982). It is concluded that afferent feedback is essential for the fine control required in this type of movement. This is consistent with Sanes and Evarts (1983) findings that unexpected brief perturbations to a limb when recalling a limb position (via forearm pronation/supination) did not effect the accuracy for large movements (30°) but did effect greater errors in accuracy for smaller movements (3°, 10°).

IIIB.25 Virtual Positions and Virtual Trajectories.

In accordance with the mass-spring model Hogan (1984) distinguished between the abstract conceptual representation of the “movement organization” and the actual physical embodiment of the “movement execution” (p. 2745). The term “virtual position” is used to refer to an intended limb position which would be produced by a new equilibrium point, and “virtual trajectory” refers to a sequence of virtual positions (p. 2746). Variable factors such as limb inertia, joint viscosity, and external forces acting on the limb may cause the execution of the actual trajectory to deviate from the conception of the virtual trajectory.

This is identical to the distinction identified in choreutics between the conceptual plan of movements (“choreutic form”) and the actual dancing, embodiment, or “utterance” of the movements (Preston-Dunlop, 1981, p. 29; 1980, p. 202). The notion of deviations created by anatomical and external factors is also identical to the theory of organic deflections identified in choreutics (see IVA.40).

IIIB.26 Multi-Joint Mass-Spring.

Most research on agonist/antagonist equilibrium points has measured movement occurring at only one joint (typically the elbow). Mussa-Ivaldi and Colleagues (1985) extended the notion of equilibrium points to refer to the total forces of muscles within a multi-joint linkage. They measured the spring-like behavior of the entire arm (resulting from the combined elastic forces of all muscles) when the hand was unexpectedly displaced during an attempt to reach at a target. Regardless of the brief perturbations, the hand still approached the target within a small elliptical-shaped range of deviation (“elastic force field”). The size of this range of deviation is considered to be an indication of the “stiffness” of the entire arm’s elasticity.

Jordan and Rosenbaum (1989, p. 731) describe this behaviour as “basins of attraction around points that correspond to desired movement endpoints”. Bizzi and Mussa-Ivaldi (1989) characterise a range of deviation around a target locus, as an “elastic-force field”, or as a “stiffness ellipse”. They point out that all Subjects had the same elliptical shape and orientation of their range of deviation, but that its overall size differed between Subjects. When continuous forces were unexpectedly added to the arm from different directions, the sizes of the ellipses changed but their shape and orientation were only slightly effected.

IIIB. 27 “Location” as Joint Angle or Distal Member Locus.

The location code might be mentally represented as the angle of the joint or as the location of the distal end of the limb. These two possibilities have been referred to in various ways.* Morasso (1981) used a two-segment apparatus which measured Subjects’ multi-joint arm movement in the horizontal plane (Fig. IIIB-2) and allowed free articulations in both the shoulder and elbow joints. Subjects’ task was to move the handle of the apparatus to target locations indicated by lights.

|

|

Figure IIIB-2. Planar positioning apparatus (adapted from Morasso, 1986, p. 18). |

__________

* The locus as either the distal member versus the joint angle is referred to as “the ‘extrinsic’ space of the hand” (coordinates of the distal end of the limb) versus the “‘intrinsic’ space of the joints” (joint angles) (Morasso, 1986, p. 21), as “spatially referenced coordinates” versus “anatomically referenced coordinates” (Soechting, 1987, p. 38), as “extracorporeal space” versus “corporeal space” (Hogan, 1984, p. 2747), as “hand coordinates” versus “joint coordinates”, or as “the metric of the environment” versus “the metric of the musculoskeletal system” (Bizzi and Mussa–Ivaldi, 1989, pp. 770–771).

__________

Velocities of shoulder and elbow joint articulations did not occur in any regular pattern but varied depending on the direction of the movement. This absence of a regular pattern is taken as an indication that these components are not actively controlled. However, the velocity of the hand exhibited an identical pattern for all movements regardless of direction. This regularity of the behaviour of the hand motion is taken as an indication that this is the component of the movement which is being controlled. Morasso (1981, p. 224) refers to this as “spatial control” of movement (as opposed to joint-angle control). Likewise, Vaina and Bennour (1985) computed the requirements for visual recognition of body movement and found that representing arm movement as the path of the hand was much more efficient than representing arm movement in terms of joint angles (p. 227). They also recommended that the recognition of movements be based on “biological constraints” which limit the variety of body movements which can occur (p. 224; see IVA.70).

Similarly, Bernstein (1984, pp. 106-117) argued that the “principle of equal simplicity” indicates that movements which are equally “simple” to produce must be mentally represented and produced in the same way. A movement “trace” (p. 106) (a geometric pathway of the hand such as a star or circle) can be transformed in a variety of ways (eg. sizing, translation, rotation; see IIID) and these transformations can often be executed as simply as the original (just as accurate, just as fast). The joint and muscle usage can differ widely between the different transformation, however the exterior spatial form is essentially identical. Thus, according to the principle of equal simplicity, the movement and its transformations are not produced by specifying and controlling muscle contractions or joint angles (since these are variable depending on the transformation) but are produced by controlling the exterior spatial form (since this is constant regardless of the transformation) (see IIID.25). This is comparable to results found with switched-limbs in spatial positioning tasks in which locations are accurately recalled regardless of the body use (see IIIB.12).

In contrast, Hollerbach and Colleagues (1987) demonstrate how regular patterns of joint articulation velocities can be identified according to a principal of “staggered joint interpolation”. Thus, motor control might also specify commands in terms of joint angles. In a different type of task, Soechting (1982) demonstrated that the perception of elbow angle was accurate only when the upper-arm was oriented vertically (elbow by the side). When the upper-arm was not vertical then the perception of forearm orientation was superior to the perception of elbow angle. This is an indication that the perception of the orientation and location of the limb in space is more fundamental to motor control than the perception of the angle of the joint. Perceptions of joint angles may be derived from the more basic perception of limb-orientations.

IIIB.31 Path Segments, Curvature Peaks.

Abend and Colleagues (1982) continued to use the multi-segment apparatus which allows free movement of shoulder and elbow joints in a horizontal plane (Fig. IIIB-2). Subjects moved their hands along curved trajectories according to three conditions: 1) Producing a curved path between two loci; 2) Following a curved path guided by a template; 3) Moving directly to a target while being forced to deviate around an obstacle. In all cases, rather than smoothly curved paths Subjects produced a series of straight or gently curved “path segments” which were separated by “curvature peaks” (a slight bump in the curve of the path). The velocity of the hand exhibited a corresponding pattern, being fastest during the path segments and slower during each curvature peak. The same pattern of path segments and curvature peaks was also identified in relatively unrestrained arm/hand movements in three dimensions (Morasso, 1983b) and in other movement studies such as a frog’s wiping reflex which is composed of five “phases” which are “punctuated by marked breaks in the limb’s movement trajectory” (Berkinblit et al., 1986, p. 595).

|

|

Figure IIIB-3. Deriving a curved path from a polygonal representation (adapted from Morasso, 1986, p. 45). |

IIIB.32 Deriving Curved Paths from Straight Strokes.

Morasso and Colleagues (1983) developed a mathematical model describing how the overall curvature of a path can be produced from a series of straight path segments. Each path segment is considered to be a “stroke” and a series of strokes to be “the sides of the polygon” (p. 85). When strokes are performed in a discontinuous manner then angular transitions occur between them. When the strokes are overlapped, beginning the next stroke before the last one is finished, then smoothly curving transitions occur between strokes (Fig. IIIB-3).

Thus, Morasso (1986) considers strokes to be the “primitive movements in the motor repertoire” (p. 44) and identifies this as similar to “spline functions” which are used to generate curved lines from a series of straight vectors in computer graphics (pp. 38-42). In spline functions “the desired shape is approximated by means of a polygon” and the amount of overlap between polygon sides determines whether the actual shape is more curved or angular (Morasso et al., 1983, p. 86). In the language of spline functions, each vertex of the polygon serves as a conceptual “guiding point” for the bodily production of the trajectory (Morasso, 1986, p. 40).

IIIB.33 Polylinear Trajectories.

Morasso (1986) also measured the trajectory of the shoulder when the trajectory of the hand takes it beyond arm’s length requiring shoulder displacement (scapula sliding across the back) and thus shifting the body’s centre of gravity sideways and/or upwards (pp. 23-24) or actually requiring the Subject to locomote (p. 34). In these cases the shoulder and hand begin moving simultaneously and move towards the same locus or along parallel directions. In either case it can be said that “the trajectory of the shoulder ‘mimics’ the trajectory of the hand” (p. 34). Both the shoulder and the hand exhibited the same pattern of path segments and curvature peaks. The shoulder path was a reduced and translated version of the hand path (see IIID.25).

IIIB.34 Locomotor Trajectories.

Baratto and Colleagues (1986, pp. 61-65) reviewed how locomotor patterns (eg. walking) have been traditionally distinguished from trajectory formation (eg. reaching and manipulating) but that these are actually derived from the same underlying process. The “direct function” of a limb or “kinematic chain” is when the proximal end is “grounded” and the distal end is free to move. In contrast to this, the “reverse function” is when the distal end of the limb is “grounded” (ie. stabilised in the environment) and the proximal end of the limb moves through space (eg. the pelvis moves forward during walking). The same equilibrium point between sets of agonist and antagonist muscles acting on the leg can push the foot backwards if the pelvis is grounded, or can push the pelvis forwards if the foot is grounded. Walking involves both the direct function (trajectories of the foot) and the reverse function (trajectories of the pelvis) and the foot prints can be considered as the “aiming or guiding points” (locus code) for the overall path.

Laban appears to have anticipated this location-based model of motor control which was later developed by trajectory formation researchers. The choreutic conception of pathways is almost identical to the trajectory formation model. Laban (1966) advised that “In describing movement, we must make a mental note of the most important intermediary positions” (p. 46) and observed that the pathway of a body movement was made up of “several outstanding characteristic peaks” which were joined by different “phases of its pathway” (pp. 27-28):

Since it is absolutely impossible to take account of each infinitesimal part of movement we are obliged to express . . . [it] by some selected ‘peaks’ within the trace-form which have a special quality. . . . [and] which strike us by their spatial appearance. (Laban, 1966, p. 28)

Accordingly, Laban (1966, pp. 23-26) conceived of each “peak” as a spatial “accent” at which point the “circuit line” changes direction, and creates a type of “spatial rhythm” or “polygonal rhythm” (p. 26). Thus, limb paths are identified as being “cornered” and entire movement circuits are considered as “tetragonal”, “six–cornered”, “hexagonal”, “seven-cornered”, “heptagonal”, “octagonal”, etc. (see IVB.33). Choreutic polygonal rhythms are identical to the trajectory formation model of polygonal representations. What Laban (Ibid.) calls the “science of harmonic circles” or “laws of interdependent circles” whereby “harmonious movement follows the circles which are most appropriate to our bodily construction”, is fundamental to choreutics and comprises the “second fact of space-movement”:

Our body is the mirror through which we become aware of ever-circling motions in the universe with their polygonal rhythms. Polygons are circles in which there is spatial rhythm, as distinct from time rhythm. A triangle accentuates three points in the circumference of a circle, a quadrangle four points, a pentagon five points, and so forth. Each accent means a break of the circuit line, and the emergence of a new direction. These directions follow one another with infinite variations, deflections and deviations. (Laban, 1966, p. 26)

Laban (1966, pp. 46-47) compares a movement path to the opening of a fan in which the “ribs” or “spokes” of the fan are analogous to the spatial accents or peaks along the pathway. A path can be performed in a “broken or angular way” by giving a “special accentuation” thus creating “imperceptible pauses” at each peak, or it can be performed “smoothly in a continuously curving pattern”. This description corresponds to the method of deriving curved paths from polygonal representations in the trajectory formation model (see IIIB.32).

Body movement has commonly been represented as a series of poses simply because of the ephemeral, transient nature of movement. For example, dance texts can do nothing else except present drawings or photos of static poses and possibly represent movement with lines signifying the path of a body-part (eg. Kirstein and Stuart, 1952). The poses selected for the description of body movements may indeed occur at the moment of a curvature peak. However, in the choreutic conception particular intermediary poses are explicitly identified as occurring at the points of curvature peaks (rather than an arbitrary segmentation of the path) and are used as conceptual guiding points for the production of curved and angular paths. Curvature peaks are linked into a series and mentally abstracted as having polygonal shapes. This corresponds closely to the trajectory formation model.

“Peaks” can also be conceived within static body poses. Anatomical points (eg. skeletal joints) can be perceived as the corners of a polygonal shape. Skeletal segments, or perceived lines between anatomical points (eg. a “connection” between the two hands) can be perceived as linear segments within the polygonal rhythm. In body movements, the spatial accents (peaks) may be perceived from the changes in speed which occur when changing direction from one path segment to the next. In static body positions the spatial accents (peaks) may be perceived from the changes of orientation from one body segment to the next (see IVB.20).

IIIB.51 Motor Control of Handwriting.

Body movements occurring during the production of handwriting are typically considered to be miniature variations of the larger movement paths created by the full body (Bernstein, 1984, pp. 105-106; Laban, 1966, pp. 83–84). Therefore, models of the motor control of handwriting have developed which are compatible with the models of equilibrium points and trajectory formation.

Denier van der Gon and Colleagues (1962; Denier van der Gon and Thuring, 1965) proposed a model for handwriting according to which the relative temporal duration of strokes used to draw a particular shape or letter remains invariant regardless of the overall size of the writing. When Subjects increase the overall size of their handwriting the duration of strokes is increased by the same percentage throughout the movement. The relative timing between strokes is identical but the duration of every stroke is extended and so the writing gets larger (Wing, 1980). Therefore, the essential pattern of the movement, the particular series of strokes and peaks, remains invariant regardless of size. The velocity of pen motion is greatest during the middle of each stroke and slowest at the points of more abrupt curvature (Viviani and Terzuolo, 1980) thus confirming the same segmented structure as found in studies of trajectory formation.

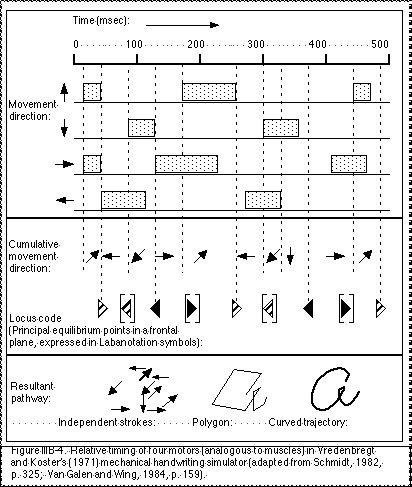

Vredenbregt and Koster’s (1971) mechanical model for handwriting demonstrated how shapes of letters can be produced with four fundamental strokes produced by four motors which move a stylus along two dimensions (vertical or lateral). Each pair of motors is analogous to an agonist/antagonist pair of muscles. Shapes of letters were controlled by the relative duration that each of the four motors is active. Transitions between the strokes was smoothed out because of the inertial forces present within the mechanical apparatus. This is analogous to the conditions in actual body movement control.

Vredenbregt and Koster (1971) represent the relative timing of the four motors in a graphic figure (Fig. IIIB-4). The action of each motor is represented as the length of a hatched area (Also in Schmidt, 1982, p. 325; Van Galen and Wing, 1984, p. 159). By changing the relative timing of the motors the shapes of the written letters could be modified in a way analogous to individual styles of writing. Here the relative timing changed the length of various strokes and so the writing appeared different, but the order and directions of the strokes remained identical so the letter could still be recognised. This type of analysis is used in this research as a basis of a taxonomy for distinguishing between categories of kinespheric paths (see Appendix XVI).

Hollerbach (1981) used the spring-like properties of muscles to explain handwriting movement (according to the mass-spring model). If the up/down and left/right motions in handwriting are thought of as being controlled by springs, then when the handwriting motion begins all four springs will begin to oscillate. If the mass attached to the springs (the fingers and stylus) is propelled into a diagonal direction (eg. up+right) then the stylus will continue to oscillate in a circle. If the “stiffness” (the amount of overall muscular tension) is unequal between the up/down and right/left springs then the oscillation will produce an oval or another shape. Different trajectories are produced by varying the order and timing of the impulses.

IIIB.52 Motor Control of Speech Articulations.

Similar locus-based theories of motor control have been developed for the movements of speech. The basic speech sounds are termed “phonemes”. Each phoneme might be produced by a particular movement of the tongue and mouth. However, the articulatory movements to produce a particular phoneme will be altered by the previous position of the articulators. That is, articulatory movements for a given phoneme vary depending on the surrounding phonemes. This is referred to as “the problem of motor equivalence in speech” that is, “achievement of relatively invariant motor goals [a phoneme] from varying origins” (MacNeilage, 1970, p. 182).

The movements required to produce a particular phoneme may be varied slightly because of a simultaneous preparation to produce the following phoneme. This overlap of phoneme movements (“coarticulation”) allows phonemes to be joined together in smooth rapid sequences (Benguerel and Cowan, 1974; Kent and Minifie, 1977; Moll and Daniloff, 1971; Öhman, 1966). However, a huge amount of information would need to be stored in order to encode all possible movements. This same problem occurs in other motor activities such as playing a piano. The movement to a particular key will always be dependent on the previous key.

MacNeilage and DeClerk (1969) used electromyographic (EMG) recordings of muscular involvement during the production of phonemes. It was observed that the EMG pattern for a particular phoneme is variable depending on the adjacent phonemes. However, the final position of the tongue during each phoneme was identical regardless of adjacent phonemes. Therefore MacNeilage (1970, p. 182) proposed that speech is controlled “by an internalized space coordinate system which specifies invariant ‘targets’”. The production of a phoneme is not considered to require a particular movement, but rather the production of a particular position of the tongue and mouth. The location of the target is stored in memory and movements are spontaneously generated in order to attain the target (Also in MacNeilage, 1973; MacNeilage and MacNeilage, 1973).

IIIB.53 Stimulus-Response Compatibility.

In a simple demonstration of “stimulus-response compatibility” Subjects are required to press a right or left button with their right or left hand in response to a visual or audio stimulus in the right or left sensory field. When stimulus and response are both on the right, or are both on the left (compatible), then the response time is less than if the stimulus is on the right and the response is on the left, or vice versa (incompatible) (Brebner et al., 1972; Simon, 1969; Wallace, 1971).

The compatibility of the response (pressing the button) might be based on the bodily right or left hand or the spatial right or left position of the button. To distinguish these possibilities in tests with visual and audio stimuli Subjects crossed their arms so that the right hand pressed the button on the left and the left hand pressed the button on the right (Brebner et al., 1972; Callan et al., 1974; Simon et al., 1970; Wallace, 1971). In other tests only the fingers were crossed (ie. the right hand on the right side presses the left button) or sticks were held in each hand which crossed and pushed the button on the other side (Riggio et al., 1986). In all cases the compatible (fastest) response was to the button in the same spatial position (right or left) as the stimulation, regardless of whether it is the bodily right or left hand, or whether the hand was to the right or left of the Subject’s midline. This indicates that compatibility is based on spatial locations rather than particular body parts.

These results led to the “coding hypothesis of spatial S–R compatibility, which says that the relative spatial positions of stimuli and responses are encoded and compared irrespective of the anatomical response organs” (Heister et al., 1990, p. 121). Similarly, the “spatial coding hypothesis” posits that the location of the stimuli and the location of the responding body-part are both coded relative to external space (Umiltá and Nicoletti, 1990, p. 106).

If the hand is turned over (forearm pronation / supination) then the spatial position of the two fingers will be reversed from when the palm is turned up versus when the palm is turned down. In both these positions the spatial position of the finger and button determined which was compatible, regardless of which finger was used (anatomical position) (Heister et al., 1986; 1987). Thus, the compatibility effects are biased on the spatial position rather than the anatomical position.

The spatial distance between the two response buttons and the anatomical distance between the two responding body-parts (eg. the ring finger and index finger versus the thumb and little finger) can each be varied, closer or farther. In this case the spatial distance also determines the size of the compatibility effects, regardless of anatomical distance (Heister et al., 1990, pp. 122–126).

However, when the response buttons are not arranged in the lateral dimension but are placed in a line along the vertical or sagittal dimension then compatibility cannot be based on right/left spatial position (since it is unavailable). In this case compatibility effects occur according to the anatomical position of the responding body-part regardless of which button is pushed (Ehrenstein et al., 1989; Heister et al., 1990, pp. 128-131; Klapp et al., 1979). These results led to the “hypothesis that an anatomical right/left distinction becomes effective [in compatibility] if the right/left distinction between response positions is eliminated” (Heister et al., 1990, p. 127).

Thus, compatibility will tend to be based on spatial locations, regardless of which body-parts are used, but when this information is not useful (eg. the response buttons are not in the same dimension as the stimuli) then compatibility can also occur according to the anatomical positions of body parts (Heister et al., 1990, pp. 131–136).

The influence of anatomic mapping is evident in all studies of compatibility. Reaction-times are slower overall in conditions when the anatomical right/left is not identical with the spatial right/left. This is assumed to arise because of a “mismatch” between the spatial code and the anatomy code (Heister et al., 1990, p. 133). In other situations when the body or head is tilted away from vertical during the compatibility task there is an increased tendency to rely on anatomical locations (Ládavas and Moscovitch, 1984). In similar tasks when the head was tilted compatibility effects occurred according to either spatial or anatomical position depending on which cues were most readily available for the Subject (Heister et al., 1990, pp. 135-136). Thus, in stimulus-response compatibility effects it appears that the spatial location code is most dominate, but that an anatomical code can be used when the body is in an unfamiliar orientation or when a clear spatial location code is not obvious.

IIIB.54 Spatial Motor Preprogramming.

The primacy of location information is also seen in studies where the direction of movement can be prepared for and planned in advance before other aspects of the movement (ie. distance, body-part usage) are known. This indicates that the basis of the mental representation of motor information is independent of the body-parts used or the size of the movement.

Rosenbaum’s (1980) Subjects used arm movements to push buttons varying along three attributes: 1) The body-part to be used (right or left hand); 2) The direction to be moved (forward or backward); 3) The distance to be moved (near or far). Subjects were told beforehand about one of the attributes and this precue would (theoretically) allow this particular bit of information to be prepared in advance. After time was given to preprogram this bit of information the other two bits of information were given and the time required for Subjects to initiate the movement (reaction time) was measured.

Rosenbaum (1980) found no difference in reaction times between the type of precue (direction, body-part or distance). However several problems with Rosenbaum’s experiment have been identified (Goodman and Kelso, 1980; Larish and Frekany, 1985; Zelaznik, 1978; Zelaznik et al., 1982). For example, secondary tasks (translating the colour of a light into the location to be moved to) were not accounted for and the number of choices required at the moment of movement initiation were not equalised across conditions.

In Larish and Frekany’s (1985) improvement of Rosenbaum’s experiment, regardless of the type of precue Subjects always chose between two possible locations (2-choice reaction time). Either one, two, three, or no attributes (body-part, distance, direction) were given as precues. When the direction was precued the time required to initiate the movement was always shorter than when the direction was not precued. The reaction time when body-part and distance were both precued (direction unknown) was no faster than when nothing was precued. Sometimes Subjects were falsely precued (the precue was wrong) and so this information would have to be re–programmed before the movement could be initiated. False cues about direction resulted in longer reaction times than false cues about body-part or distance. In addition, false cues about all three attributes resulted in the same reaction time occurring after a false cue about the direction only.

These results indicate that the first attribute of a movement to be prepared, and thus the most elemental code, is the direction to be moved towards and that body-use and distance are prepared later. Body-use and distance cannot be planned without knowledge about the movement direction. Larish and Frekany (1985, p. 185) characterise this as a hierarchical relationship between these three parameters. Comparable results by Klapp (1977) and Proteau and Girouard (1984) also demonstrated that movements can be prepared without any “muscle-specific” (ie. body-usage) information.

The location code for a movement trajectory specifies only a series of locations to be moved through by the distal end of a skeletal linkage. In most cases many articulations must take place in mid-limb and proximal joints to accommodate for this intended trajectory. This is the problem of “intersegmental coordination” (Golani, 1986, p. 608; Jeannerod, 1981), also discussed as Bernstein’s (1984) problem of “motor equivalence” (Berkinblit et al., 1986; Kelso et al., 1979b); that different limb configurations could all accomplish the same path of the distal end of the limb. The problem for motor control is how these many possibilities of articulations within the skeletal linkage are coordinated while accomplishing a goal of the distal end.

Automatic, “reflexive” interactions among muscles have been observed to provide accommodation for the path of a distal body-part. This aspect of movement coordination, “the ability to regulate movement activity over many sets of muscles and different limbs” (Smyth et al., 1987, p. 100) are considered as “coordinative structures” of the motor system. These provide the bodily articulations required to achieve the locations planned for a distal point of the limb.

The theory of coordinative structures (see Appendix VII) is compatible with the mass-spring model (IIIB.20). A target location can be specified for a movement (ie. an equilibrium point for an entire multi-joint linkage) without specifying the particular muscular actions. Functional groupings of muscles automatically accommodate to the desired target according to an available “library” of reflex movements (Easton, 1972). Original thoughts on coordinative structures are usually credited to the famous Soviet physiologist N. A. Bernstein who’s writings from the 1930s onwards have led to a conception of motor control sometimes called “The Bernstein Perspective” (Fitch et al., 1982; Tuller et al., 1982; Turvey et al., 1982) and has received recent reattention (Whiting, 1984).

Bernstein (1984) observed that muscles automatically cooperate during movement and referred to these as “structures of movements”, “integral formations” or “integration of movements” which are “The most important feature implied by ‘motor co-ordination’” (p. 83). The terms “synergy” (Kelso et al., 1979a; and others) or “coordinative structure” (Easton, 1972; 1978; and others) are variously used to describe a group of muscles crossing several joints which function cooperatively together as an integrated system.*

__________

* Coordinative structures are variously described as “a group of muscles often spanning a number of joints that is constrained to act as a single functional unit” (Kugler et al., 1982, p. 60), “a group of muscles functioning cooperatively together” (Turvey, 1977, p. 219), “functional synergies” (Sheridan, 1984, p. 49), “functional groupings of muscles”, “synergies”, “muscle collectives”, “muscle linkages” and as “a group of muscles whose activities covary as a result of shared efferent or afferent signals” (Kelso et al., 1979a, pp. 229–235).

___________

An analogous concept is a “kinematic chain” (Bernstein, 1984, p. 82), or “kinematic linkages” (Turvey, 1977, p. 219) used to refer to a group of body segments and joints linked in a series. “An appendage such as an arm or a leg is a biokinematic chain -- that is, it consists of several connected links, so that a change in an one link affects the other links” (Turvey et al., 1982, p. 248). The notion of a kinematic chain implies some amount of coordination among its parts.

Similarly, Bartenieff and Lewis (1981, pp. 21, 105) referred to a “kinetic muscular chain” which exhibits an active coordination within the linkage and is described as the quality of being “connected”. They consider this to be the “body” aspect which compliments the “spatial” aspect of choreutics.

Bernstein (1984, p. 91) describes movement “coordination” as having the qualities of “homogeneity, integration and structural unity”. One of the simplest examples of a coordinative structure, or the “integration of movements”, is the “gradual transfer of innervation” within a muscle collective:

The simplest and most easily observed phenomenon in this category [of integrated, coordinated movement] is the appearance of gradual and smooth redistribution of tensions in muscular masses, which is particularly clearly expressed in cases of phylogenetically ancient or highly automatized movements. A muscle never enters into a complete movement as an isolated element. Neither the active raising of tension nor the . . . inhibition in antagonistic subgroups is, in the norm, concentrated in a single anatomical muscular entity; rather, there is a gradual and even flow from one system to others. (Bernstein, 1984, p. 83)

Bartenieff and Lewis’ (1980, p. 247) similar example is the even gradation of rotory articulation in the shoulder which can occur as the arm moves in a large circle. This gradation of innervation is also similar to Laban’s law of “flowing-from-the-centre”:

. . . allowing the movement to flow out from the centre of the body. Such an arm-movement then has the sequence: torso impulse, leading of the shoulder blade, upper-arm, fore-arm, and lastly the hand. This movement comes out from the body-centre and ensures a light volatility. (Laban, 1926, p. 18)

A hierarchy of coordinative structures are envisaged from the lowest order reflexes in single muscles and reciprocal muscles, to higher order muscle collectives governing actions within an entire limb, to even higher order reflexive patterns of the entire body. These are not fixed (“knee-jerk”) responses but can be “tuned” (adjusted) in accordance with environmental conditions (Berkinblit et al., 1986; Evarts and Tanji, 1974; Gurfinkel et al., 1971a).

A full review of functional relationships within muscle collectives is out of the scope of this research (for an introduction see Appendix VII). Coordinative structures are considered here to be an essential body counterpart to the spatial location-based motor code.

IIIB.71 Automatic Processing of Location Information.

Location information also appears to be fundamental in the recall of words or pictures. If the identity of an item is remembered then the location of that item will also likely be remembered (even though there had not been any intention to try to remember the location). This has been shown for a variety of stimuli and conditions.* When a focused intention is made to remember the locations they are recalled no better than when no intention is made (Schulman, 1973). Therefore it is concluded that “location information is automatically coded into long-term memory storage in the sense that active processing is not required” (Mandler et al., 1977, p. 10). This appears to be a basic trait of perception rather than being learned since the same results have been found for age groups from kindergartners to adults (Ibid).

__________

* Automatic processing of location information has been shown for verbal passages within a page or within the page sequence (Rothkopf, 1971); words arranged within spatial arrays (Schulman, 1973); locations of small toys, objects, and words arranged in a matrix (Mandler et al., 1977; Pezdek et al., 1986); and the right/left position of a line drawing or word (Park and Mason, 1982).

__________

IIIB.72 Locus-specific Memory Storage.

When abstract line drawings are presented in the same location, then the last presented drawing is recognised better than earlier presented drawings (recency effect), however when each drawing is presented in a separate location then all drawings are recognised equally well (Broadbent and Broadbent, 1981). Similar effects occur in verbal cognition. Verbal information presented from a variety of locations is recalled better than if it is presented entirely from the same location (Rothkopf et al., 1982). Distracting words spoken from the same location as other words to be recalled cause greater interference than if spoken from a different location (Crowder, 1978). These results indicate that parallel memory resources are provided for separate spatial locations or regions. Items in memory interfere in as much as they are encoded from the same environmental location.

IIIB.73 Locus-based Mnemonic Strategies.

Many mnemonic strategies have a long history of use, from the ancient Greeks through to modern times, which are based on mentally establishing a relationship between an image of an item-to-be-remembered and a particular imagined environmental location (eg. a room in a building). During recall Subjects mentally travel through the imagined space and recall the items present at each location. A variety of these strategies have been reviewed in detail by Bower (1970a), Paivio (1979, pp. 153-175), and Yates (1966).

A variety of research indicates that mental representations of spatial information are based on individual locations. For example, the final location of a body movement can be recalled better than the distance moved and the location of one body-part can be recalled (virtually) just as well with a different body-part. These effects indicate that spatial locations are recalled rather than particular movements. The mass-spring model for motor control provides a theoretical basis for a location code. The elemental unit of body-movement is thought to be a single motion toward a new “equilibrium point” between tension in agonist and antagonist muscles. Each equilibrium point comprises one elemental location. A location code is also evident in studies of “trajectory formation” where measurements of path curvature and velocity revealed that a path is composed of “path segments” separated by “curvature peaks”. The “primitive movements in the motor repertoire” are thought to consist of path segments (“strokes”) and curvature peaks (“guiding points” for the production of the trajectory). Angular or curved transitions depends on how much two consecutive strokes are “superimposed”. The “abstract representations” of a body movement are posited to be cognitively planned according to a series of locations in which “the desired shape is approximated by means of a polygon” (one location at each polygonal corner), and then “the sides of the polygon are generated and superimposed” in actual body movement.

Similar location-based models have been developed for handwriting production, motor control of speech, stimulus-response compatibility, spatial motor preprogramming, and in visual and verbal memory. Coordinative structures are identified as the body-level counterpart to the spatial-level of the location code.

These models of motor control and spatial cognition give psychological validity to the choreutic conception where Laban identified “‘peaks’ within the trace-form” and “phases of its pathway”. Accordingly, kinespheric paths and poses are conceived as being polygonal-shaped (one “peak” at each polygonal corner). Curved or angular trajectories are produced depending on whether successive strokes are smoothly blended together or if the curvature peaks are abruptly accented. This choreutic conception is virtually identical to the trajectory formation model.